An increased use of computers was arguably the single most significant development for Disney animation during the 1980s. Computer assisted animation had kept costs more or less under control for The Great Mouse Detective and Oliver and Company, helped with several of the effects shots in The Little Mermaid, and provided one of the few aspects anyone in the animation department was willing to remember about the hell that had been The Black Cauldron. Up until the very end of the decade, however, computer assisted animation was only used for selected shots and effects.

That was about to change with The Rescuers Down Under, an otherwise forgettable film that formed a Disney milestone: it was the first Disney animated film to use the Computer Animation Production System throughout the entire film.

For this experiment, the producers chose to stick with something relatively safe—a sequel to the 1977 The Rescuers. Disney had, granted, never made a sequel to any of its animated films before this, but The Rescuers had been one of their few box office successes during their doldrum years of the 1970s and 1980s. The ending to The Rescuers had also left open the possibility for more adventures—indeed, prior to making the film, Disney had been toying with the idea of making an animated cartoon show based on The Rescuers. That show ended up becoming Chip ‘n Dale Rescue Rangers, leaving The Rescuers sequel free to play with the new possibilities offered by computers, specifically something called the Computer Animation Production System.

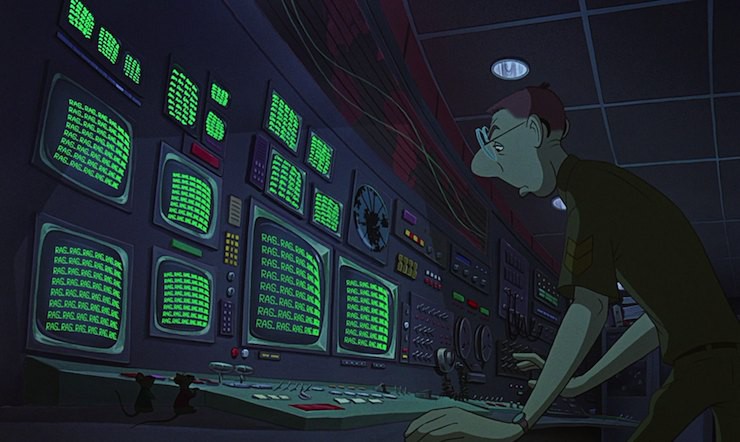

The Computer Animation Production System, or CAPS for short, was used to digitally ink and color all of the animated cels. It completely eliminated the need for hand inking or hand coloring, except for single animation cels produced to sell at various Disney art stores. It also allowed animators to create zoom effects—something that had been difficult to achieve in previous animated films—things that looked like live action tracking shots, and multiplane camera shots without the use of a multiplane camera. And, most importantly from Disney’s point of view, it meant that The Rescuers Down Under and subsequent films could be made for considerably less money; it’s estimated that the CAPS probably saved Disney about $6 million in development costs for The Lion King alone.

CAPS was not, however, a Disney invention. It had been developed by a small firm called Pixar, recently spun off from Lucasfilm (in 1986, in the aftermath of George Lucas’ financially crippling divorce), which had recruited (by some accounts) or outright stolen (from other accounts) computer scientists from the 1970s Computer Graphics Lab, at the time eager to create the very first computer animated film. Somewhat surprisingly, that computer animated film never emerged under George Lucas’ direction (surprising considering the heavy use of computer animation in later Star Wars prequels).

Instead, Pixar mostly spent the 1980s quietly dazzling artists with various small animated things—a tiny sequence in Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan, a short about a couple of lamps called Luxo Jr.—and snatching up animator John Lassester when he was fired from Disney for being too obsessed with computers. (It’s ok, computer geeks everywhere. There’s a very happy ending to this, I promise, even if that ending is several posts ahead.) With a computer animated short, and more or less stable financial leadership under Steve Jobs, Pixar was starting to contemplate abandoning its unprofitable hardware division to focus entirely on computer animated films. Something about toys, maybe. Or bugs.

Pixar’s full length computer animated films were a few years off, however, as was an extremely acrimonious dispute with Disney, which we’ll get to. For now, Pixar worked with Disney animators to create The Rescuers Down Under, experimenting with the process of combining hand and computer animation.

As a result of this, quite a bit of The Rescuers Down Under contains scenes that have no other purpose except to show off the CAPS process and what it could do—the opening zoom sequence where the camera zips across a field of flowers, for instance, or the sequence showcasing Miss Bianca and Bernard desperately running on spinning deep tread tires.

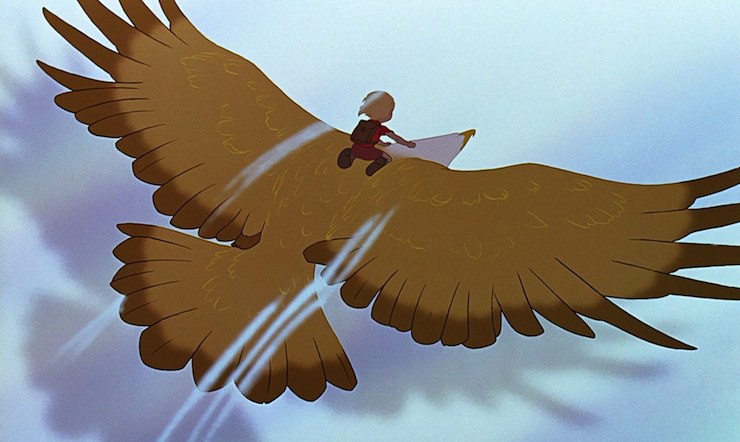

And that’s a bit of a problem—one that showcases the central issue of The Rescuers Down Under. It’s a film with a lot of plot, but not necessarily a lot of cohesive plot, continually flipping from one plot to another, creating multiple pacing issues. It’s not that the basic story—Miss Bianca and Bernard heading off to Australia to rescue an adorable kid kidnapped by an evil poacher—is bad. But the film keeps skipping here and there, never really connecting its characters until the final sequences, and often getting off track, as in a long and frankly unnecessary sequence where Wilbur the albatross is getting treated by various medical mice, which borders uneasily between comedy and horror, with bits that even John Candy’s generally hilarious voicing of Wilbur can’t make amusing. Plot holes abound: Bernard, for example, saves the eagle’s eggs with a clever trick that requires that a small mouse have the ability to carve eggs out of stone with his bare mouse paws in about, say, ten minutes. It’s not that Disney films are exactly known for their realism, but The Rescuers Down Under often wants to have it both ways: realistic depictions of the issues involved when three little mice go up against a Big Bad Human, and this.

The film also ends rather abruptly, leaving several unanswered questions, though it’s very possible that the creators figured they would be following this film up with another sequel. And I can’t explain a surprising lack of Australian accents in a film mostly set in Australia—one or two of the animal characters sound Australian, as does little Cody’s mother (mostly heard, not seen) and the very dashing kangaroo mouse Jake, apparently meant to be the mouse version of Crocodile Dundee. Everyone else sounds rather American.

Including the villain, poacher Percival C. McLeach. I can handwave the accent, partly because I can’t think of a reason why a poacher in Australia wouldn’t be American, and mostly because McLeach is American because he’s voiced by legendary actor George C. Scott, who explains that he didn’t pass third grade for nothing in gloriously strident tones.

Trivial yet Titanic sidenote: George C. Scott later played Captain Edward J. Smith in the 1996 Titanic miniseries. Bernard Fox, who has a very small role in this film, had a brief cameo playing Colonel Archibald Gracie IV in the 1997 Titanic movie and earlier had an uncredited small role in the 1958 A Night to Remember, another Titanic film. I believe that makes The Rescuers Down Under the only Disney animated film, so far, to have two actors connected to three different Titanic projects.

Anyway. If I can let the accent go, I do, however, find myself raising an eyebrow at the actual villain, who despite Scott’s voicing, never quite manages to enter the ranks of the great Disney villains. Perhaps because on the one hand he’s too evil—beyond the poaching issue, he kidnaps and threatens a little kid, a pretty over the top reaction—and yet somehow not evil or powerful enough.

And because I’m not entirely sure that he really is the main villain here. The Rescuers Down Under dances around this, but the chief issue seems to be, not McLeach, but rather the complete helplessness of law enforcement not staffed by mice. Cody tells us, over and over, that the Rangers will get the poacher, and yet the only Rangers we end up seeing are the ones who (incorrectly) inform newscasters and his mother that little Cody has been eaten up by crocodiles. In general, they seem, well, not inept exactly—since, to repeat, we hardly see them—but absent or powerless. None of this would be happening, the film suggests, if the Rangers were doing their job.

This is hardly the first time that Disney had created animated films with inept or missing police characters. In Robin Hood, for instance, the villains are—technically—the law enforcement. And many of Disney’s greatest villains exist in a world without a law enforcement capable of standing against them—Sleeping Beauty‘s Maleficent, for example, can only be taken down by magical creatures, not the royal armies. When the world does include capable law enforcement—One Hundred and One Dalmatians, for instance, or even The Jungle Book—the villains take active steps to avoid them. Here, although McLeach does kidnap Cody, his main motivation is not to prevent Cody from telling the Rangers everything, but to get information from Cody. And when Cody does escape, he notably doesn’t head to the Rangers, despite his repeated claims that the Rangers can shut McLeach down. He heads to the eagle’s nest alone.

Combine this with the sideline medical story, where the medical mice insist on treating an albatross and drugging him despite his protests, and how easy it is for the RAS mice to temporarily take over United States military communications, and The Rescuers Down Under presents, probably unintentionally, one of the most uneasy looks at the establishment since, well—since at least Robin Hood, and possibly ever in the Disney canon. Most strikingly, the film does not end—as did The Rescuers—with any shots showing Cody returning home with the help of authority figures, or with shots of the other kidnapped animals getting to return to their rightful places. Or at least a nice zoo. Instead, it ends with a number of loose ends, and John Candy’s voiceover telling us that, not only has the established order not been restored, he, an albatross, is still unhappily guarding an eagle’s nest and watching eggs hatch.

This isn’t to say that the the film doesn’t have a number of good or hopeful things. The romance between Miss Bianca and Bernard, here possibly threatened—gasp! by a very dashing Australian mouse—is still sweet and charming and remarkably adult. I’m a bit surprised that it’s taken Bernard what, 13 years to pop the question to such a charming mouse like Miss Bianca, but not at all surprised that his wedding proposal is generally used for bits of high comedy and pathos. It’s kinda difficult to propose, even in an elegant New York City restaurant, when you are constantly having to dash off and save people. Minor characters like a koala and a monitor lizard are comic delights. The bit where the Australian mice telegraph for help is fun, as is the sequence where mice around the world struggle to pass on the message—showing, by the way, that they could interrupt U.S. military procedures in Hawai’i whenever they want to, which is rather alarming, but let’s move on. I am very pleased to note that in the intervening years, Africa now has representatives from all of its countries; well done, RAS. (And Disney for correcting this.) Cody is considerably less annoying than the previous child in peril in The Rescuers. The bits where Cody rides the eagle—created through CAPS—soar.

But The Rescuers Down Under did not. It enjoyed only a tepid performance at the box office, possibly because it was competing against the wildly successful Home Alone. Flanked as it was by two far more successful Disney animated features, The Rescuers Down Under swiftly sank into obscurity, a little astonishing for a film whose innovative computer work was to form the basis for so much of Disney’s later animation.

If the film itself sunk into obscurity, the computer programming techniques used to develop it did not. Indeed, a number of animators were already carefully studying its sequences, in between doodling pictures of little lions, soaring carpets, and—in 1990—a roaring, raging beast.

Next up: a little Christmas detour, followed by a break, before we return in the new year with Beauty and the Beast.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.